HISTORY

Kumihimo are deeply connected to various aspects of Japanese culture; including religion, etiquette, the preforming arts, apparel, and furnishings. They’ve changed with the times, finding new applications, and developing new designs and techniques accordingly.

The actual beginning of the full-fledged spread of kumihimo was during the Asuka and Nara era when culture from continental Asia was introduced to Japan.

Asuka and Nara Periods (538-794CE)

A New Vitality Comes to the Land of the Rising Sun

It’s believed that braiding techniques from the Asian continent took root in Japan during the Nara period. Early examples of naragumi, sasanamigumi, karakumi, andagumi, and other varieties of kumihimo can be still be found in Nara’s Shosoin, and Horyuji temples. The kumihimo of this era, while ostentatious, feature a characteristically restrained color palate.

Heian Period (794-1192CE)

An Infusion of Japanese Skill and Refinement

While during the Nara period people were content to follow the standard methods of braiding, the Heian period was an era for the pursuit of more diverse artistic expression.

Combining previously existing techniques to create new ways of producing kumihimo, the era was also host to the development of variegated dyeing techniques. The fruits of all this innovation were used by noblemen to hold the scabbards of their longswords, to hold together armor, for binding scrolls, and for hanging scrolls, for hanging amulets around the neck, and various other purposes.

Greater Depth and Complexity: A Triumph of Creativity

Making use of the braiding techniques that emerged in the Heian period, a wealth of new kumihimo styles were created during the Kamakura period.

As style representative of the period, kikkogumi is an excellent choice. It was widely used in the samurai armor of the day. Additionally, patterns such as saidajigumi and chioningumi can be found inside Buddhist statuary from this time.

It appears that no new techniques were developed during the Muromachi era, however the high-level techniques developed in the Kamakura period continued to flourish.

Modern Craftsmanship: The Rebirth and Reformation of Ancient Forms

The production of kumihimo, which declined during the Warring States (or Sengoku; c. 1467 – c. 1603CE) period, began to flourish once again as Japan entered the Edo period. This revival of techniques that had fallen out of use was rather extraordinary.

Worthy of special mention is the fact that the main use for the kumihimo of the day was as a means of holding the scabbard of a sword tightly to the waist. Such cords are almost exactly the same length as the obijiime, which is still used to hold the obi – worn as a belt with a kimono – in place to this day. For this reason, various kumihimo styles used for such purposes were transformed, and new methods of production were born.

Examples of new styles created in the Edo period include kainokuchigumi, koraigumi, and jinaikigumi.

The technique known as ayadashi was also born in this era. It allows for the addition of intricate patterns and even lettering to kumihimo designs. The emergence of a wealth of new patterns coupled with the development of the sophisticated culture of the Edo period is well documented in the literature of the day.

Moving Towards the Present: Technique and History Without End

The primary demand for kumihimo products, which had been for use with scabbards and as cordage, abruptly declined with the prohibition of swords in the Meiji Restoration (1868CE). Having lost most of their business, producers of kumihimo saw the obijime used to hold women’s obi in place – which were gradually becoming mainstream fashion – as a means of survival. Throughout the Meiji period, as the otaikomusubi style for women’s obi became the norm in Japanese-style clothing, the kumihimo as obijime in turn became a necessity. Such products soon made up the great majority of kumihimo production in this era.

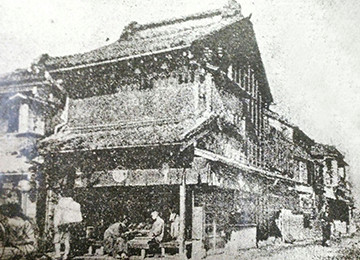

The site of our main branch, the Ikenohata area surrounding Yushimatenjin shrine, was established long ago as a bustling commercial district. At the start of the Edo era it was in the southwest quarter of Edo (the former name for Tokyo), and was also home to Kaneiji, a temple modeled after Enryakyji temple in Kyoto. Part of the greater Ueno area, it was a favorite leisure time destination for Edo townspeople.

In this period kumihimo production was classified alongside yarn producers, as part of the cordage trade. Established in 1652, Domyo has been pursuing the same craft ever since. There are no clear records remaining of the exact circumstances of our founding, but it is believed that a samurai retainer from the Takada fiefdom in the Echigo area who laid down his sword to open a business was the one who started it all.

Moving forward, in the mid 18th century Shimbei Domyo, was the first of his name to head the business. Since then we’ve kept it in the family for 10 generations. In the time of the first Domyo, the primary demand for kumihimo was for use in samurai armor and as a way to affix the scabbard of a sword, and there were many cordage producers in Edo, and it was the craftsmen of this industry who produced the bulk of the kumihimo on the market. Moreover, the samurai of the period were a major part of the development of new braiding techniques. It was widely held among them the armor they wore should be armor that they made themselves, and the ability to braid kumihimo was considered a necessary skill. Techniques described in military texts from the period are a valuable source of information on they way they were made at the time.

Sword straps produced with the ayade method

By the middle of the Edo period, the prospects for samurai were poor in comparison with the merchant class. Out of economic necessity, the production of kuihimo became a side job for extra income, which is how their techniques came to be to be passed on. According to my grandfather, the 7th generation Domyo Shinbei, his grandfather, the 5th generation Domyo Shinbei, commonly visited the homes of samurai families to acquire examples of kumihimo they had made. With the aid of the historical and technical study of the samurai of the past, kuminimo production techniques reached an incredibly high level. In turn this enabled the techniques of the Edo period to reach new heights.

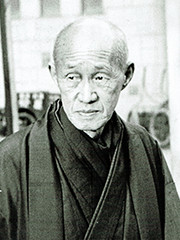

The 5th generation Domyo Shinbei

In this climate of change Domyo remained in Ikenohata, preserving the handmade legacy of master craftsmen, while constantly striving to further refine the production of kumihimo. However, with the national ban on swords, the customary demand for kumihimo as sword straps and wrapping for sword hilts all but vanished, and producers shifted focus to making objime, essential items for women’s kimonos. In the Meiji era, narrow braids with metal fittings were the most common, but there was a gradual move towards use of the thicker cords that were once used to carry swords. With products that preserved the essence of the original kumihimo used by samurai, the Meiji and Taisho eras were the age when these braided masterpieces became synonymous with the obijime used in women’s fashion.

Early example of an obijime

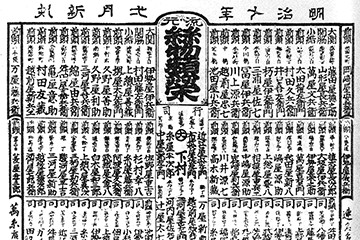

Since its initial founding on through to the present day, Domyo has never been a large-scale operation. In a list of textile producers by output volume published in 1877 (the 10th year of the Meiji period) our shop was not that far above the lowest ranks. At the time the shop was apparently known as Echizenya, which is how it was listed in the actual document. There were still many kumihimo establishments in Tokyo at this point, ranging from the biggest shops to individuals working at home. If you had to say what kind of a shop it was, you could call it a place that was well-known by loyal fans and those in the know rather than a mainstream operation.

List of textile manufacturers by production volume

Around the middle of the Meiji era, the influx of western culture and the ongoing process of modernization had brought things to a point where the people of Japan began to widely re-examine the beauty of their traditional culture. It was then that the desire grew to preserve traditional handicrafts – even the humble kumihomo, which had never been thought of as being as important as the things that it was used to hold in place – that had been rediscovered as the extremely high-quality, artistically valuable items that they truly were. At the same time, the 5th generation Domyo Shinbei is known to have been in contact with Okakura Tenshin, a figure at the center of this movement. As our shop was located near the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, and Japan Art Institute, it seems that it became a sort of salon, which brought together people of culture. What’s more, this was also the period in time when the 6th generation Domyo Shinbei began his study of historic kumihimo preserved at Shosoin in Nara. There is even a story that he received permission for the project from Mori Ogai himself, by way of the Imperial Household Museum.

Our shop in the Meiji period

At this our work as a kumihimo producer included filling increasing numbers of requests from museums and Buddhist temples all over the country in order to restore important cultural treasures. Successful industrialists with a deep interest in Japanese culture who collected valuable antiques, also began to make requests to reproduce traditional kumihimo for their private collections. The 7th generation Domyo Shinbei also documented an order from Barron Masuda in hid work, “Himo,” to restore a piece done in the Itsukushima style that has apparently decayed so badly that it would have disintegrated if you blew on it. Despite this he was able to determine its construction and get the job done.

Even in such an environment, Domyo continued to innovate, producing many new designs for obijime and other items based on our unique esthetic vision. There were also quite a few items with traditional kumihimo patterns available, which continue to be displayed proudly in our store 100 years later.

Design sketches by the 6th generation Domyo Shinbei

As the Showa era began, the availability of kumihimo made by the hands of artisans further declined as mass-produced machine-made alternatives grew in popularity. Spurred on by modernization and industrialization the production of kumihimo shifted from the use of trade secrets passed on from master to apprentice, to more generally available methods. Alongside technologies developed for the weaving and knitting of textiles, the mass production of braided cords led to their widespread use in a number of applications. In spite of this, handmade kumihimo didn’t completely disappear. As items of true value, they continue to be made to this day.

Our shop at the beginning of the Showa era

In the prewar period of the Showa era, the 7th generation Domyo Shinbei began to examine kumihimo from an academic standpoint. Such study was also conducted during the preceding 6 generations, but it was done with the aim of preserving the hand done work of the artisans who produced them. It was all about examining the construction and coloration of the originals in order to create faithful reproductions. But then the 7th generation Domyo Shinbei – making the most of his natural scholarly tendencies – began to systematically evaluate and classify of the different styles of kumihimo. With the previous work, “Himo,” as a starting point he undertook the creation of numerous academic treatises on all things kumihimo which were widely read by members of the community. Just the ones I still have on hand include, “The Kumihimo of Japan,” “Thoughts on the Cultural History of Japanese Cordage,” “The Emergence of Braiding Theory and the Aspirations of the Archaeological Community,” “The Japanese Craft of Kumihimo,” and “The Relationship Between Cultural Assets and Kumihimo.” His compositions large and small were varied and numerous. In addition to these efforts, he also studied the kumihimo found at Shosoin and Chuusonji; not just to examine and reproduce them accurately, but also in order to determine their significance in terms of the history of kumihimo production itself.

Replicas of kumihimo from Soshoin

Shinchusonjigumi – An obijime pattern which improves upon the design of a fragment found in the grave of Fujiwara No Hidehira (1033-1187CE)

Another goal was to have kumihimo seen as a traditional Japanese craft in its own right, as opposed to its former status as something ancillary to other historic handicrafts. He established the systematic study of kumihimo by examining its history, technique, and artistic theory. His continued efforts both before and after the war have helped to shape the way we think about kumihimo to this day. Indeed, we’re still studying, and continue to make new discoveries to add to the work already done over so many generations.

Postwar shop interior

Although our shop was founded in the Edo period – starting with the work done by the samurai of the day as a foundation – examination of historical kumihimo from all over Japan was also conducted in the Meiji era. The products we make today are used as everyday like the obijime, and in other traditional clothing applications, as well as more unusual items like cords for ceremonial purposes, and even western-style neckties and various accessories, but they’re all built on the foundation that was formed in the earliest days of Japanese history.

Out show in the Showa period

Domyo is located Tokyo’s Ueno area in the Ikenohata neighborhood. Construction of our new main branch, which was completed in February of 2016, is a modern 5-story concrete building with a design inspired by traditional Japanese architecture. Simultaneously classic and modern, practical and emotional, we envisioned it as a structure that combined various seeming contradictions. It features a kumihimo archive, an area for dyeing, a design studio, and a workroom. Kumihimo production begins on the top floor, working down to the ground floor where the finished products are sold. The building itself serves as tool for the braiding process.

Our shop in the present day

Present day interior